What We Talk About When We Talk About Books by Leah Price — Book Review + Discussion

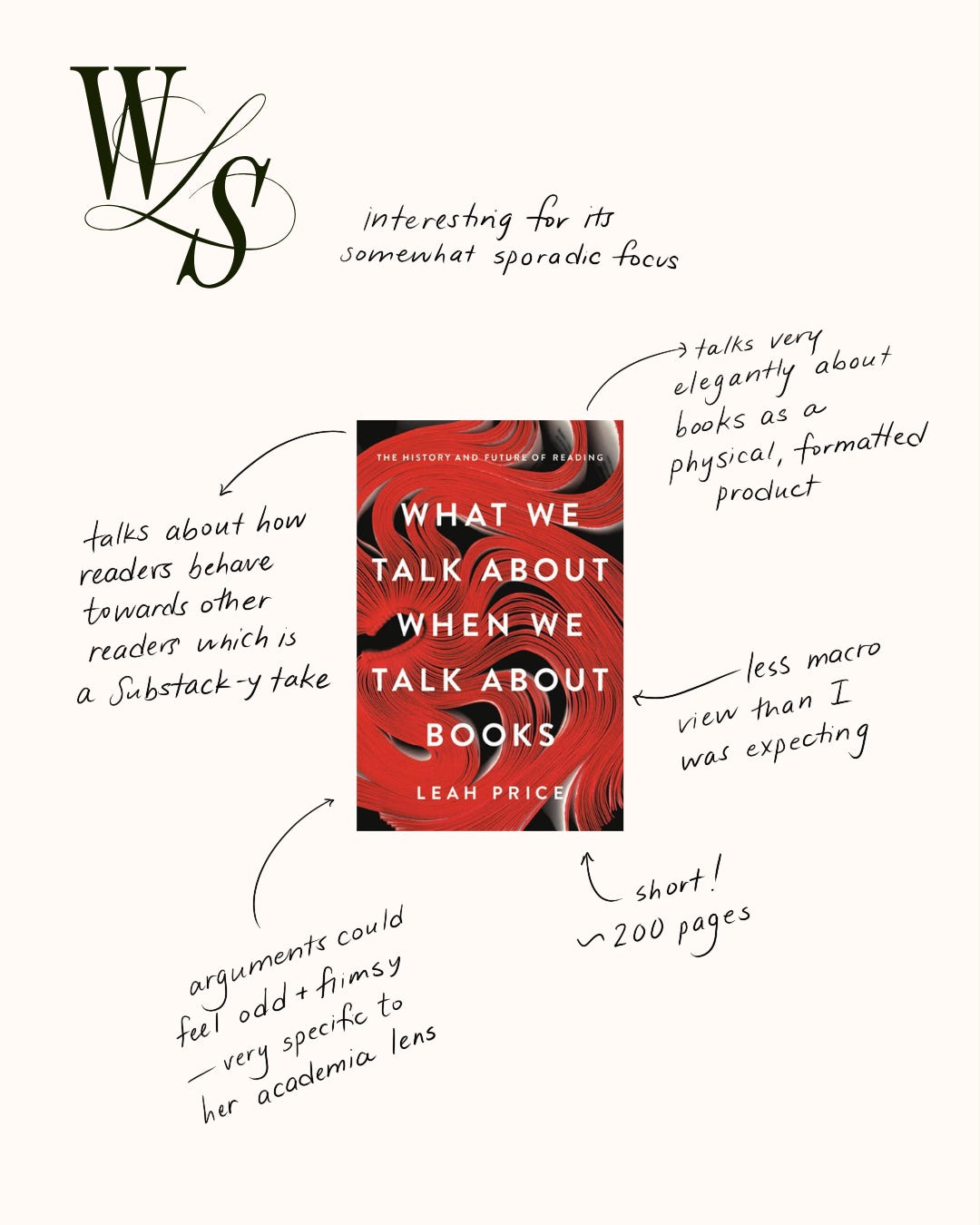

This meandering analysis of how we treat books and reading focuses mostly on the physical object. Some strange turns make it worth talking about too.

The paradox is that essayists who task novel reading or poetry reading with saving or changing their lives wager that we’ll spend a good portion of our lives reading…essays. As Clay Shirky points out, “an entire literature about the value of reading Proust is now more widely read that Prout’s actual oeuvre.”

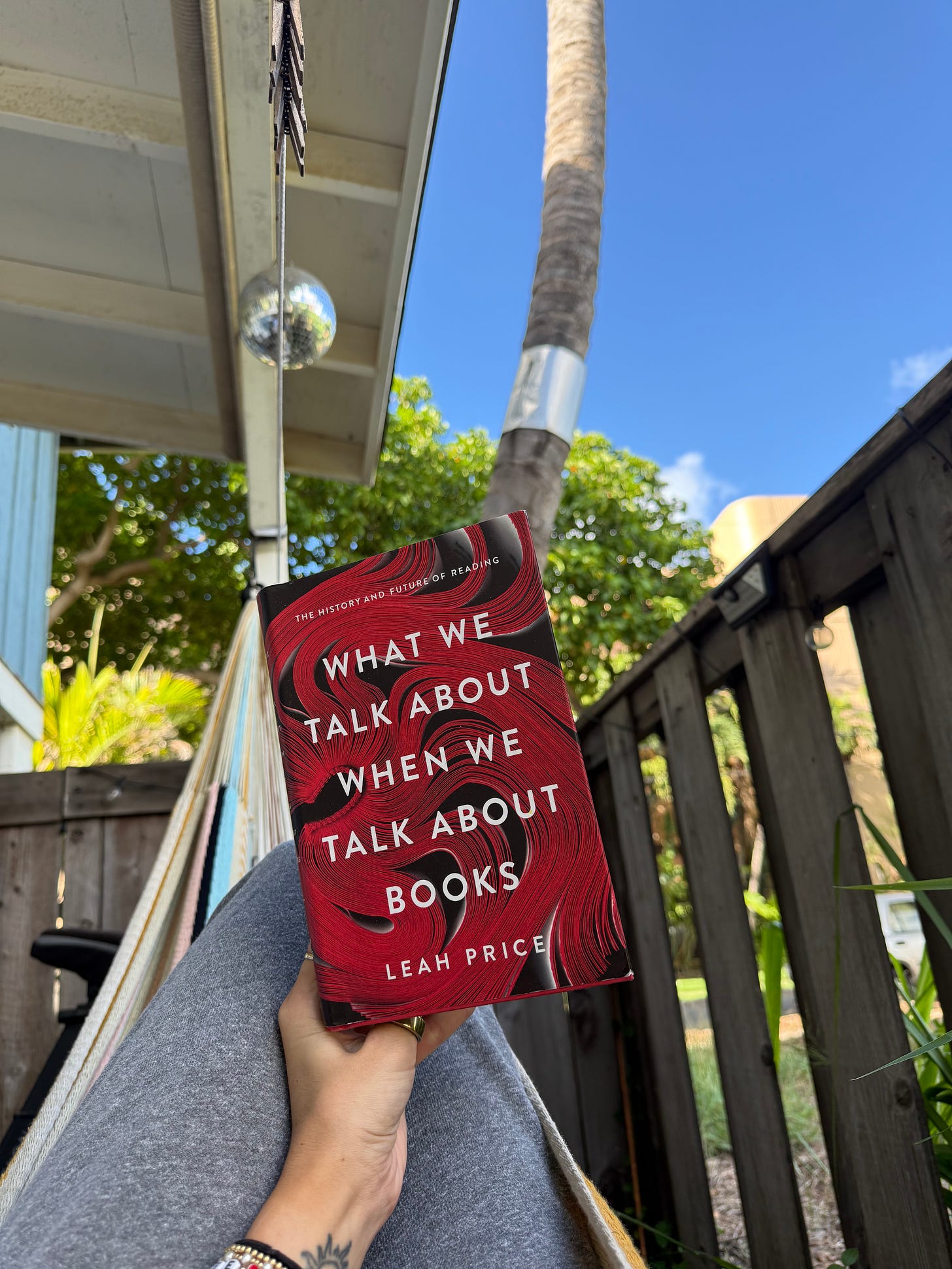

Book: What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: The History and Future of Reading by Leah Price

Release Date: August 19, 2019

Publisher: Basic Books

Format: Hardcover

Source: Bought

Reports of the death of reading are greatly exaggerated—

Do you worry that you’ve lost patience for anything longer than a tweet? If so, you’re not alone. Digital-age pundits warn that as our appetite for books dwindles, so too do the virtues in which printed, bound objects once trained us: the willpower to focus on a sustained argument, the curiosity to look beyond the day’s news, the willingness to be alone. The shelves of the world’s great libraries, though, tell a more complicated story. Examining the wear and tear on the books that they contain, English professor Leah Price finds scant evidence that a golden age of reading ever existed. From the dawn of mass literacy to the invention of the paperback, most readers already skimmed and multitasked. Print-era doctors even forbade the very same silent absorption now recommended as a cure for electronic addictions. The evidence that books are dying proves even scarcer. In encounters with librarians, booksellers and activists who are reinventing old ways of reading, Price offers fresh hope to bibliophiles and literature lovers alike.

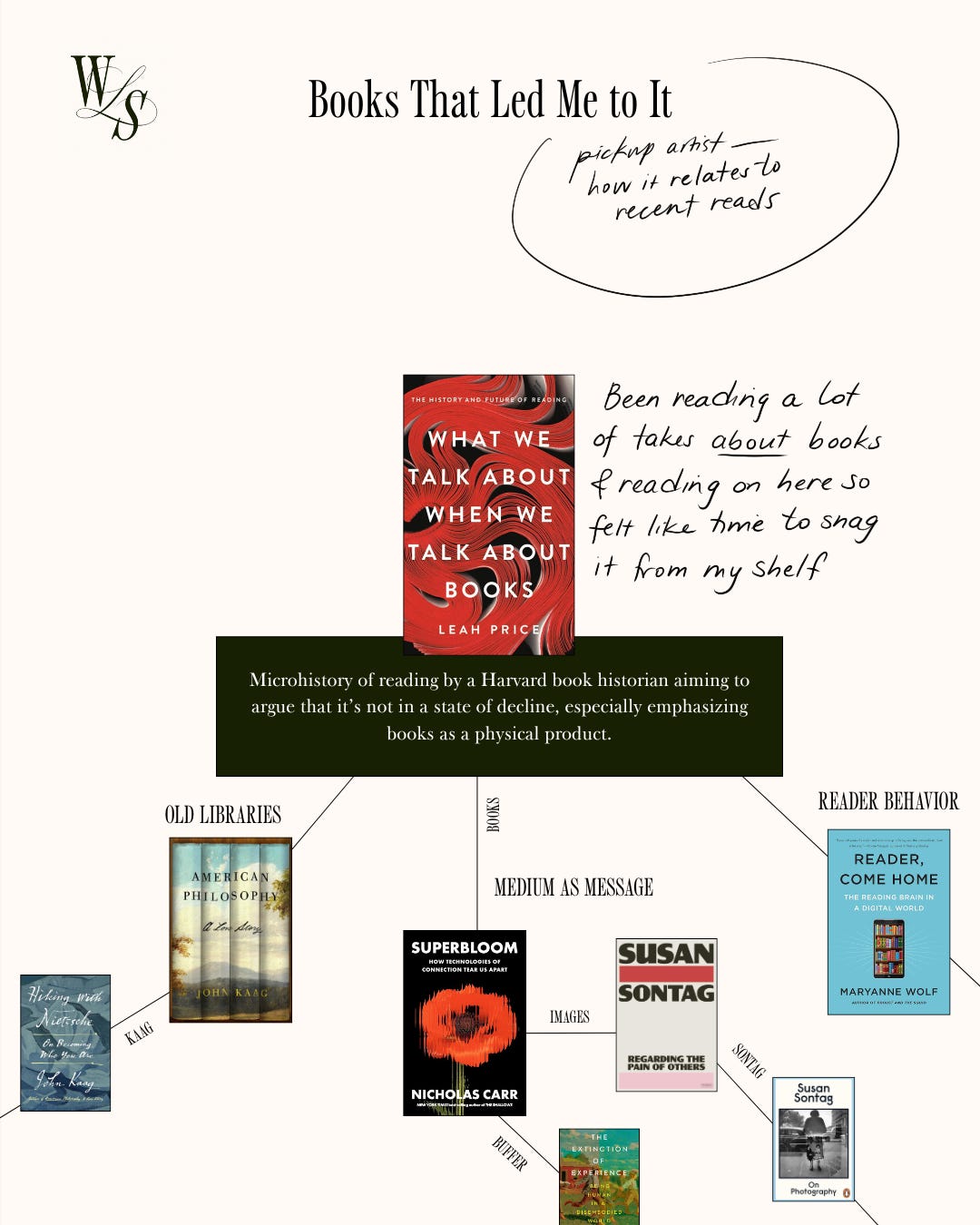

Why I Picked It Up

Recently, I’ve loved reading about reading. Books about books have been very up my alley, both on the author and consumer side, and I’ve clicked into any related essays. Many people here seem just as concerned with reader identity as with the literal content of the books themselves.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Books has been on my shelf for ages, and I stumbled across my underlines in the first chapter—but I apparently never finished it. I got through it yesterday while taking a break on my hammock.

RELATED: Pickup Artist: The Pitt, The Plague, and Peter Matthiessen

About the Book

First, Leah Price makes a clear distinction between books as text and as product, which I don’t think enough people talk about (beyond the usual “do audiobooks count?” discussion.) Parts reminded me of Nicholas Carr’s Superbloom in emphasizing that the medium makes the message.

Leah Price stresses frequently that our romanticization of reading in print specifically isn’t historically accurate. It’s not like we’ve always sat down with an analog book—Substack loves the word analog—and been blissfully uninterrupted and immersed within that experience. As she notes, we’ve always gone through books and highlighted, extracted, butchered them. Certain volumes were always intended to be borrowed or skimmed or (fun fact that delighted my trivia brain) certain genres were even historically restricted to time of day.

A lot of this book is rooted in Price’s focus on the preservation of physical books, which reminded me of John Kaag’s American Philosophy: A Love Story. Much of her analysis stems from examining the literal wear-and-tear of certain volumes over time and working backwards to determine how people read; certain sections fall apart more, or show multiple readers’ fingerprints, while others go untouched.

Sometimes, I thought her writing could be bold or flowery in a way that didn’t entirely feel accurate, sacrificing nuance in favor of a satisfying parallel line. She’ll toss around segments like “bytes rather than bombs,” “books as both savior and martyr,” or “the history of reading is also a history of worrying” which all sound elegant—but occasionally a little abrupt in the context of the sentence they’re used in. Certain sweeping points feel very opinionated and specific to her particular lens as a Harvard professor, like being disappointed by students reselling textbooks to the university bookstore at the end of the semester instead of keeping them. (That’s so cost-related that it almost feels silly to cite as evidence for any sort of reader behavior.)

Her chosen topics are surprising and a little odd—like, for example, a full chapter on bibliotherapy and the implications of putting books on the same field as therapeutic medication. It’s a good, supplementary read to understand how we read probably because it picks such touch points. Because its focus feels a little strange at times, I’d also caution readers to know what they’re getting into because it’s not as zoomed-out as the synopsis makes it sound.

I don’t necessarily believe her data about reading’s decline being overblown. Some information feels cherry-picked or dated. And then there are a few moments which reminded me eerily of this absolutely bizarre tangent bell hooks goes on about Harry Potter in The Will to Change, which lost me for a similar looseness.

Like Price’s comments characterizing bookstagram as scantily clad (I just blatantly wracked my brain trying to figure out what she’d been seeing in 2019???) or on Fifty Shades of Grey embodying “an English major’s craving for constraint”? Just a little weird in a way that felt like it took an abstract argument of hers one step too far for belief.

A volume like this is also—unfortunately—relatively rooted in time. Some of her observations and data (as the book came out in 2019) are already dated and incorrect.

Still, it’s a good overview of our attitude towards books as a physical object. I was expecting it to feel more holistic as a microhistory, but What We Talk About When We Talk About Books gave me food for thought.

Some Points I Appreciated

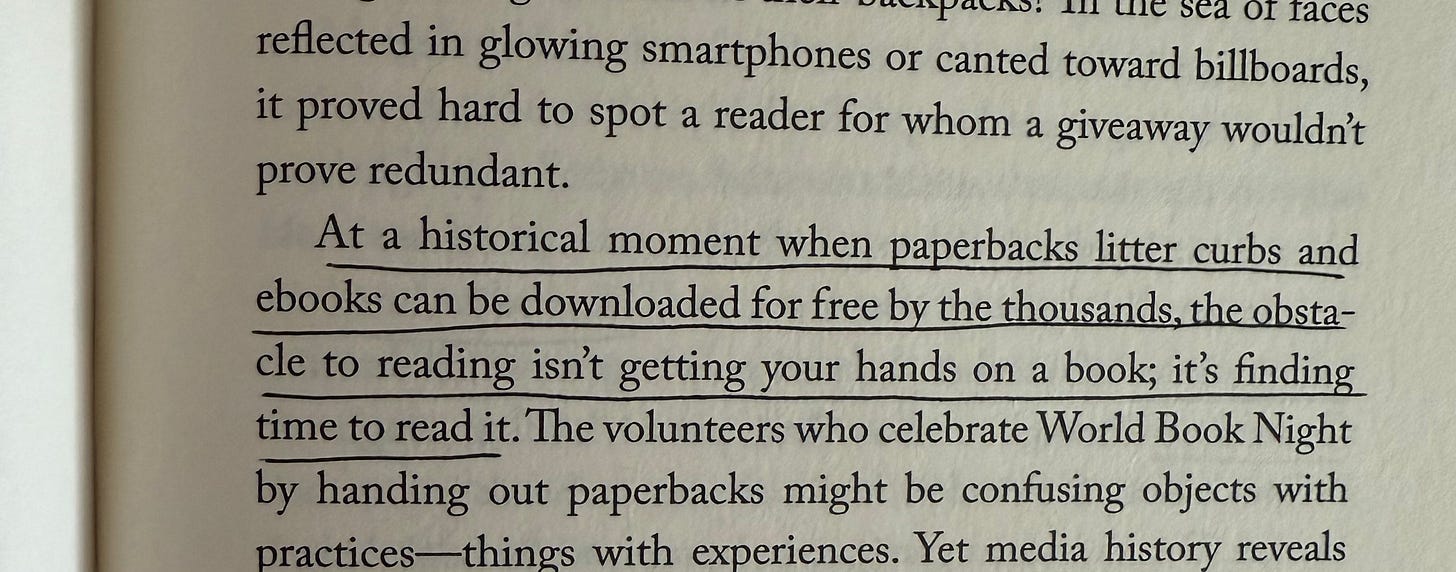

I did appreciate her emphasis on books as a physical product. For example, a big factor in publishing right now is that paper prices rose so much during COVID-19 and never went down, so production cut costs. The paper’s flimsy; the binding falls apart more easily. Books as products don’t feel durable enough. From the author side, agents and editors will warn you especially against swollen word counts because shorter books are selling better thanks to corrupted attention spans and the lowered cost of producing them. That extra 10,000 words in a manuscript could be the kiss of death.1

Price makes an excellent point about how reviewers on Amazon don’t always distinguish between the text (“I loved this thriller”) vs. the product and its fulfillment (“shipping was late, my copy had smudges on it”), whatever, and that’s an avenue in which books are markedly different from other consumer goods.

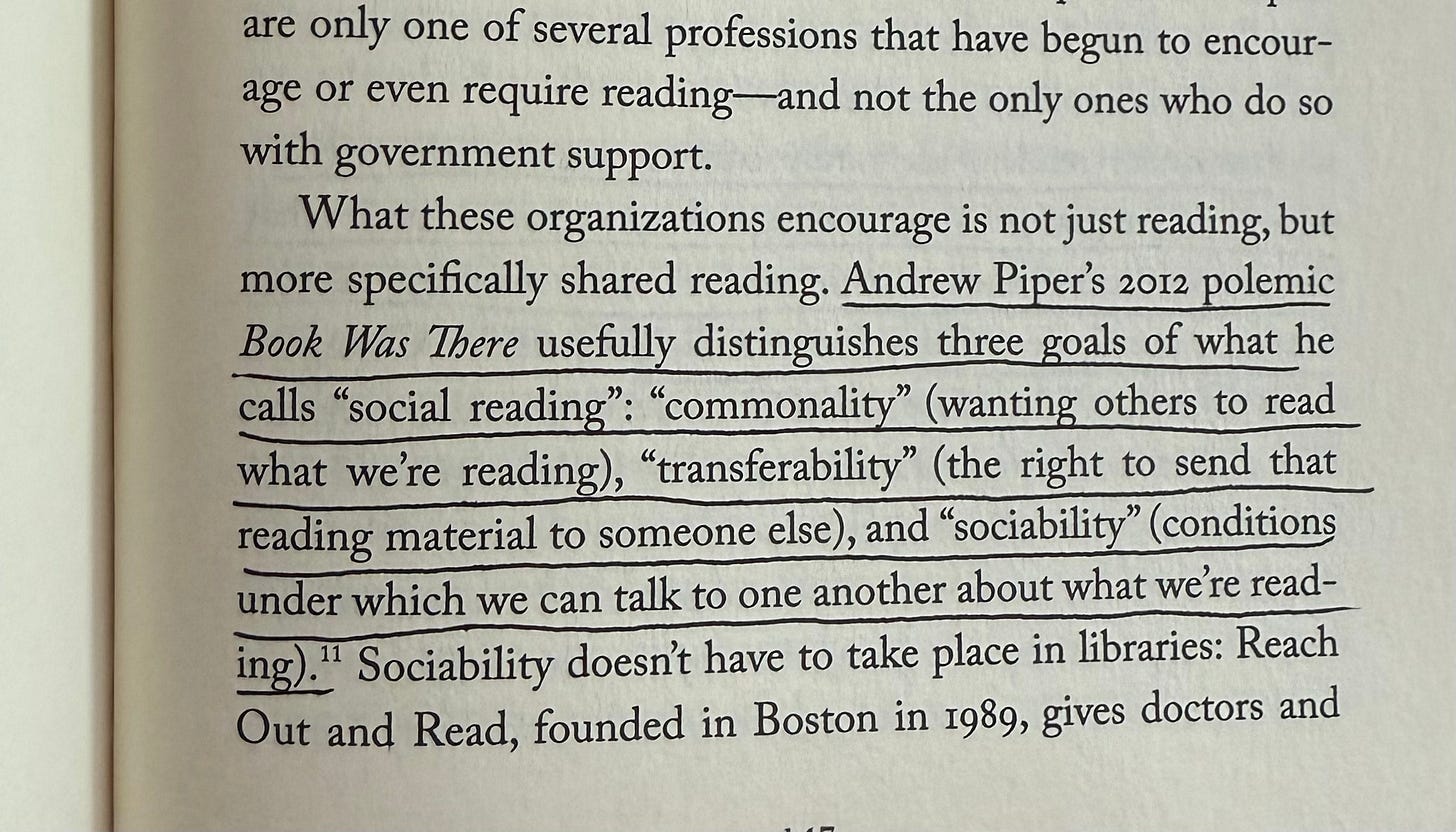

I also loved certain descriptions of reader behavior and ownership, like how we changed the cultural tendency to lend books rather than buy them. Or that, at one point, the type of books you gifted would shift. Once, people thought it best to share annotated copies, and a well-loved book was deemed most flattering to someone. Later, it was deemed more polite to gift a pristine, fresh copy for the reader to mark up by themselves.

She talked a lot about the social element of readers wanting other people to read, which of course is familiar to many on Substack, and what that entails.

Overall Thoughts

What We Talk About When We Talk About Books was an interesting read for anyone who enjoys considering our behavior around books. While I was expecting to be more macro, it narrows in on the physical product aspect of format. I wouldn’t use as your main source of literary history and behavior (and I have other recs for that), but it’s nice for the edge case considerations and trivia bits.

My studio art background loves conversations around format, especially as it relates to consumable culture now—and how we discuss it here. (See: my curiosity about Substack’s bizarre preference for quotes within quotes.) And it does have some banger lines about how we express our own reading behavior that will resonate with ye writers of Substack.

I absolutely feel like my debut novel will be shorter than it should be (not just said for sentiment) vs. other books in its genre years back, simply because my word count rule is smaller than other authors got to work with a few years back.